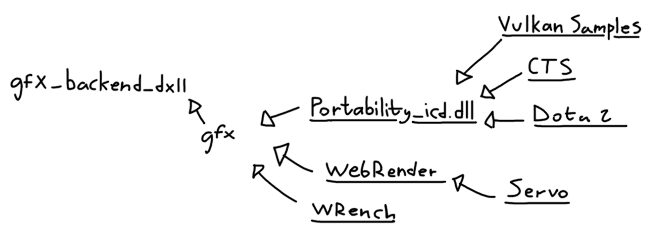

For this years GSoC I (@fkaa) worked on implementing the DirectX 11 backend for gfx, a graphics API which translates to Vulkan, DirectX 12 and Metal.

WebRender is the web content GPU renderer used by Servo, the prototype browser engine headed by Mozilla. WebRender is currently looking at using gfx as an API for drawing graphics. In order for WebRender to make a switch to gfx, it would need to have wide platform support, including Windows 7, which is still a substantial part of the userbase.

So why is this useful? Vulkan already runs on all windows versions, right? Yes, but not quite. While Vulkan can run on Windows 7, not all hardware supports it, and more importantly, it does not come by default!

All of my contributions and discussion of the project can be found on github here.

Challenges

Unlike the other backends for gfx (Metal, DirectX 12), implementing this backend meant trying to shape an “old-gen” API into a “next-gen” API, rather than having all the fancy new features from the start.

One of the major goals of the backend was to be able to run on Windows 7, which only supports DirectX 11.0, which means losing out on some of the more recent features of the API.

gfx-hal essentially mirrors the vulkan API, which means a lot of existing litterature helps in understanding its API, but it also means that the specification for how it’s supposed to act is huge (the Vulkan spec is ~700 pages!). This is not too big of a problem, since a large portion of how vulkan behaves has not changed since the “old-gen” APIs:

- Pipeline stages and shading languages are mostly left unchanged (with a few additions)

Draw()calls are still calledDraw()

But there’s also a huge influx of new features which have no equivalent on DirectX 11:

- New resource management model with Memory/Heaps and suballocating

- New resource binding model with descriptor pools & sets

- Manual synchronization between resource accesses

- Render passes

- And much more.

There are also a few small inconsistensies here and there, such as the ability to clear a subregion of an image in Vulkan, rather than the whole image. All these put together can paint a pretty scary picture, but applications rarely utilize all features of the API.

Going into the details of every feature would span several pages, so I’ll describe some of the more interesting ones. The link to all the pull requests contain the implementation details, discussion and motivation of all the features.

Next-gen Memory

Any resource creation in later APIs usually have to be suballocated from a bigger, opaque piece of memory. First you allocate a piece of memory of a given size, next you create images/buffers and what have you, and finally bind the image/buffer to a piece of memory.

As you might expect, this doesn’t have an equivalent in DirectX 11 (Tiled Resources are interesting, but too new!). Since we can only create independent dedicated resources, we have to emulate this.. by simply placing all the resources together in our “fake” memory.

struct BoundResource {

resource: ComPtr<ID3D11Resource>,

range: Range<u64>,

}

struct Memory {

resources: Vec<BoundResource>,

...

}

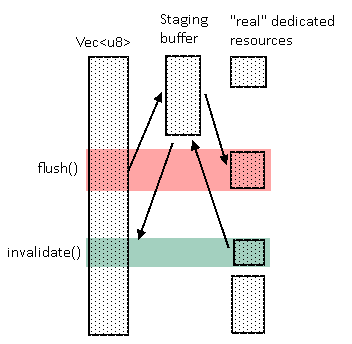

This might sound simple, but Vulkan allows memory to be written to by mapping the memory, which returns a writable (and readable) pointer to the memory. Even more, you can have the pointer mapped forever. DirectX 11 does have resource mapping, but since we dont have anything covering the entire range of the memory we can only get disjoint mapped ranges. Not only that but these mapped ranges cant stay mapped forever and have to be unmapped when in use.

This leads to a quite unfortunate thing in our implementation in that we have to duplicate the whole memory range on the host side (CPU) in order to allow for a permanently mapped pointer, and for resource binding to be able to have some initial data from the memory range it was bound to.

There’s two important types of CPU-visible memory types in vulkan; coherent and non-coherent. The only difference between these two is that with non-coherent memory you need to explicitly call flush() and invalidate() to make changes visible to the GPU and CPU respectively. This means that for coherent memory, since we don’t know whether there was anything written to or if there are going to be reads after execution, we need to upload and download the whole memory range if it’s used in a command buffer.

Copying

A very common operation in vulkan is to copy from a buffer to an image. Since DirectX 11 only supports copying from buffer to buffer and image to image we have to implement this behaviour using compute shaders, which can have read/write access to both buffers and images.

Synchronisation

In a way, we are quite lucky here. Later APIs hand over the reins for synchronising resource accesses to the user. This means that if you write to a texture and later read from it, you need to explicitly make sure that these two operations don’t overlap.

In earlier APIs (like DirectX 11) this is all handled internally by the driver, so this frees us of implementing pipeline barriers and subpass dependencies for example.

Debugging

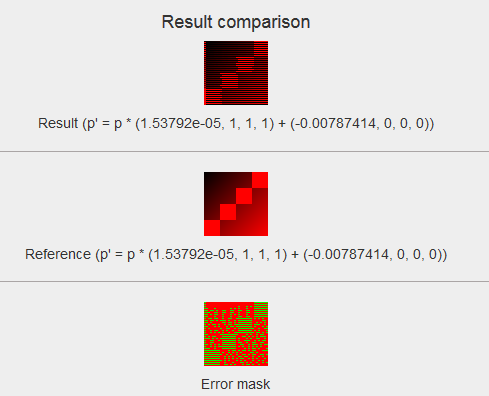

The tool of the trade is often RenderDoc, allowing you to inspect the contents of a frame. If you’re not familiar with graphics programming, the most common way that stuff gets to the screen is by way of draw calls or compute shader calls (also known as dispatches), this means that finding the source of a graphical glitch can often be traced from a draw or dispatch call. From there we can further classify bugs:

- Some resources were not bound

- Resources were bound, but data is incorrect

Both of these can be caused by a feature not yet implemented or implemented incorrectly. This kind of method for hunting bugs makes it quite easy to implement a minimal feature set required to run an application, while also hardening the backend at the same time. This is made even nicer by the fact that we can compare our results with a “ground truth” version which is using the system Vulkan driver.

Testing

A crucial element to testing the backend was gfx-portability which is part of the Vulkan Portability Initiative, which allows us to provide a implementation of a subset of Vulkan, exposing the same C API functions from Rust. This lets us run Vulkan applications than can indirectly test our backend.

Conformance Test Suite

Khronos has made their extensive test suite for Vulkan conformance open source on GitHub. This means that we can run the tests with our backend to see how much coverage (and conformance) of the Vulkan API we have with our portability wrapper.

There are over 300,000 (!) tests in the CTS, though the bulk of them come from testing format permutations and a lot depend on features which might not yet be exposed in the backend.

As of now the DirectX 11 backend has 33,019 passing tests and 43,379 failures/crashes

WRench

WebRender directly interfaces with gfx and also has some reference tests similar to the CTS. These are quite specific to webrender (lots of blend modes and box shadows and whatnot).

In total there are 137 tests and as of writing this the DirectX 11 backend passes 126.

Playing games instead of working?

Almost! Around the start of GSoC Valve anounced they would be shipping MoltenVK on Mac to provide a Vulkan implementation for Dota 2. Coincidentally, gfx also had a Metal backend at the time, and used the gfx-portability library to test the backend.

Although the end result would be quite pointless (Dota 2 already uses DirectX 11 directly), it seemed like a great way to test the backend against a real world usage of the API. It took a while to get over the initial hurdle of getting it to launch without crashing, but after that it was smooth sailing.

Servo

All of this leads up to testing the backend in Servo, which draws content using WebRender. There’s not much more to say for getting servo to run, since it only depends on WebRender for drawing, so if WebRender works, so should Servo.

What’s left?

There are still a few missing features not yet implemented for both the CTS/WRench suite and Dota to look correct and unfortunately in-game pictures looks a bit less impressive. Outstanding issues are posted at GitHub and ready for work:

- Constant buffer offsets

- Host visible images

- Unaligned copies on small formats

- More copy shaders

- Descriptor arrays

- Texture swizzling

It was a lot of fun to work on this project and it’s amazing how much you can learn from doing a shim implementation of an API. Big thanks to my mentor Dzmitry (kvark) and the rest of the gfx contributors for a great GSoC experience!